Schiller is an oddly shaped lunar impact crater located in the southwestern sector of the Moon. To the east is the crater Bayer and to the southeast is Rost.

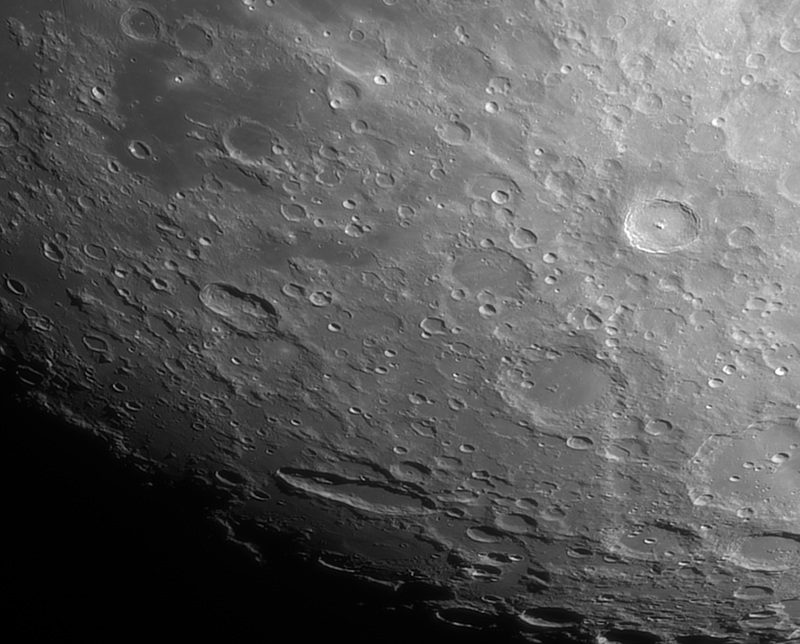

The rim of Schiller has an elongated shape that is amplified by its proximity to the lunar limb. The long axis lies along a line running northwest–southeast, with the wider girth located in the southeastern half. There is a slight bend in the elongation, with the concave side facing to the northeast. Schiller appears to be a fusion of two or more craters and bears a superficial resemblance to the footprint left by a shoe.

The crater rim is well-defined, with a terraced inner wall and a slight outer rampart. At the southeastern end, a smaller crater is connected to Schiller by a wide valley. Most of the crater floor is flat, most likely due to lava flooding. There are some bright patches that are most clearly visible under a high sun angle. A double ridge lies along the center of the northwest crater floor, forming a nearly linear formation that divides the floor in half.

To the southwest of Schiller is the Schiller-Zucchius Basin, a Pre-Nectarian basin (multi-ringed impact structure).

Tycho is a prominent lunar impact crater located in the southern lunar highlands, named after the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe (1546–1601). It is estimated to be 108 million years old.

To the south of Tycho is the crater Street, to the east is Pictet, and to the north-northeast is Sasserides. The surface around Tycho is replete with craters of various sizes, many overlapping still older craters. Some of the smaller craters are secondary craters formed from larger chunks of ejecta from Tycho. It is one of the Moon's brightest craters, with a diameter of 85 km (53 mi) and a depth of 4,700 m (15,400 ft).

Age and description Tycho is a relatively young crater, with an estimated age of 108 million years (Ma), based on analysis of samples of the crater ray recovered during the Apollo 17 mission. This age initially suggested that the impactor may have been a member of the Baptistina family of asteroids, but as the composition of the impactor is unknown this remained conjecture. However, this possibility was ruled out by the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer in 2011, as it was discovered that the Baptistina family was produced much later than expected, having formed approximately 80 million years ago.

The crater is sharply defined, unlike older craters that have been degraded by subsequent impacts. The interior has a high albedo that is prominent when the Sun is overhead, and the crater is surrounded by a distinctive ray system forming long spokes that reach as long as 1,500 kilometers. Sections of these rays can be observed even when Tycho is illuminated only by earthlight. Due to its prominent rays, Tycho is mapped as part of the Copernican System.

The ramparts beyond the rim have a lower albedo than the interior for a distance of over a hundred kilometers, and are free of the ray markings that lie beyond. This darker rim may have been formed from minerals excavated during the impact.

Its inner wall is slumped and terraced, sloping down to a rough but nearly flat floor exhibiting small, knobby domes. The floor displays signs of past volcanism, most likely from rock melt caused by the impact. Detailed photographs of the floor show that it is covered in a criss-crossing array of cracks and small hills. The central peaks rise 1,600 meters (5,200 ft) above the floor, and a lesser peak stands just to the northeast of the primary massif.

Infrared observations of the lunar surface during an eclipse have demonstrated that Tycho cools at a slower rate than other parts of the surface, making the crater a "hot spot". This effect is caused by the difference in materials that cover the crater.

The rim of this crater was chosen as the target of the Surveyor 7 mission. The robotic spacecraft safely touched down north of the crater in January 1968. The craft performed chemical measurements of the surface, finding a composition different from the maria. From this, one of the main components of the highlands was theorized to be anorthosite, an aluminium-rich mineral. The crater was also imaged in great detail by Lunar Orbiter 5.

From the 1950s through the 1990s, NASA aerodynamicist Dean Chapman and others advanced the lunar origin theory of tektites. Chapman used complex orbital computer models and extensive wind tunnel tests to support the theory that the so-called Australasian tektites originated from the Rosse ejecta ray of Tycho. Until the Rosse ray is sampled, a lunar origin for these tektites cannot be ruled out, though tektites are now generally considered to have been produced by terrestrial impact events.

This crater was drawn on lunar maps as early as 1645, when A.M.S. de Rheita depicted the bright ray system.

Names Tycho is named after the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe. Like many of the craters on the Moon's near side, it was given its name by the Jesuit astronomer G.B. Riccioli, whose 1651 nomenclature system has become standardized. Earlier lunar cartographers had given the feature different names. Pierre Gassendi named it Umbilicus Lunaris ('the navel of the Moon'). van Langren's 1645 map calls it "Vladislai IV" after Władysław IV Vasa, King of Poland. And Johannes Hevelius named it 'Mons Sinai' after Mount Sinai.

Source: Wikipedia

Schiller es un cráter de impacto lunar de forma extraña ubicado en el sector suroeste de la Luna. Al este está el cráter Bayer y al sureste está Rost.

El borde de Schiller tiene una forma alargada que se amplifica por su proximidad a la extremidad lunar. El eje largo se encuentra a lo largo de una línea que corre de noroeste a sureste, con la circunferencia más ancha ubicada en la mitad sureste. Hay una ligera curva en el alargamiento, con el lado cóncavo hacia el noreste. Schiller parece ser una fusión de dos o más cráteres y tiene un parecido superficial con la huella dejada por un zapato.

El borde del cráter está bien definido, con una pared interior en terrazas y una ligera muralla exterior. En el extremo sureste, un cráter más pequeño está conectado a Schiller por un amplio valle. La mayor parte del piso del cráter es plano, probablemente debido a la inundación de lava. Hay algunos parches brillantes que son más visibles bajo un ángulo alto del sol. Una cresta doble se encuentra a lo largo del centro del piso del cráter noroeste, formando una formación casi lineal que divide el piso por la mitad.

Al suroeste de Schiller se encuentra la cuenca Schiller-Zucchius, una cuenca prenectaria (estructura de impacto de anillos múltiples).

ycho es un prominente cráter de impacto localizado en la parte sur de las zonas elevadas de la Luna, llamado así por Tycho Brahe (1546-1601).[1] Al sur de Tycho se localiza el cráter Street, al este Pictet, y al norte-noreste Sasserides.

La superficie lunar alrededor de Tycho se halla repleta de cráteres de diversos tamaños, muchos de ellos incluso superponiéndose a otros más antiguos. Algunos de los más pequeños son cráteres secundarios formados por materiales proyectados por el impacto que formó el cráter de Tycho.

Tycho es el cráter más joven entre los grandes cráteres de impacto del lado visible de la luna. Su edad aproximada es de 108 millones de años, estimada a partir de la datación de muestras traídas durante la misión Apolo 17. Esta edad sugirió en su momento que el cráter podía haber sido formado por el impacto de un miembro de la familia de asteroides Baptistina, pero como no era posible conocer la composición del aerolito, la hipótesis quedó en una simple conjetura, a pesar de que los estudios de simulación daban una probabilidad del 70 por ciento de que el cráter hubiera sido creado por un fragmento de la misma ruptura que originó el asteroide (298) Baptistina; que se creía que podía ser el responsable de la formación del cráter de Chicxulub en la Tierra, y de la consiguiente extinción de los dinosaurios. Sin embargo, esa posibilidad fue potencialmente descartada por el Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer en 2011.

El cráter tiene los bordes bien definidos y libres del desgaste que muestran los impactos antiguos. El interior tiene un alto albedo evidente cuando el Sol incide directamente sobre él. El cráter se halla rodeado de un distintivo sistema de marcas radiales y algunas de ellas alcanzan hasta 1 500 km. Debido a sus rayos prominentes, Tycho se considera como parte del Período Copernicano.

Los contrafuertes que se extienden tras el borde del cráter tienen un albedo inferior al del interior por más de 100 km. Asimismo, no se ven las marcas radiales que hay debajo. Este anillo más oscuro puede haberse formado a partir de minerales excavados durante el impacto.

La pared interior del cráter desciende abruptamente formando terrazas hasta una superficie prácticamente plana, con pequeños montículos redondeados. La superficie muestra señales de un pasado vulcanismo, muy probablemente causado por roca fundida por el impacto. Fotografías detalladas del suelo dejan ver un mosaico de grietas y pequeñas colinas. El pico central se eleva 1,6 km por encima de la superficie. Un pico menor se halla al noroeste de este.

Observaciones mediante infrarrojos de la superficie lunar durante un eclipse han demostrado que Tycho se enfría mucho más lentamente que otras partes de la superficie, haciendo del mismo un "punto caliente". Este efecto es causado por la diferencia con los materiales que cubren la superficie del cráter.

El borde del cráter fue elegido como objetivo de la misión Surveyor 7. La sonda robótica aterrizó suavemente al norte del cráter en enero de 1968. La nave realizó comprobaciones químicas de la superficie del cráter, hallando una composición diferente a la de los mares lunares. Para este el principal componente resultó ser anortosita, una roca ignea rica en aluminio. El cráter fue también fotografiado en detalle por la sonda Lunar Orbiter 5.

De 1950 a 1990, el experto en aerodinámica de la NASA Dean Chapman y otros científicos postularon la teoría del origen lunar de las tectitas terrestres. Chapman utilizó complejos modelos de ordenador orbital y extensas pruebas de túnel de viento para apoyar la teoría de que las llamadas tectitas australasianas se habrían originado durante el impacto que formó el cráter Tycho, a partir de los materiales eyectados en dirección al cráter Rosse, que generaron el denominado "rayo de Rosse", una de las marcas más prominentes del sistema de marcas radiales de Tycho. Sin embargo, análisis isotópicos más recientes han descartado esta teoría, confirmando el origen terrestre de las tectitas.

Este cráter apareció en mapas lunares en fechas tan tempranas como 1645, cuando Anton Maria Schyrleus de Rheita detalló el brillante sistema de marcas radiales.

Denominaciones Tycho recibe el nombre del astrónomo danés Tycho Brahe. Como muchos de los cráteres de la cara visible de la Luna, este nombre le fue dado por el astrónomo jesuita italiano Giovanni Riccioli (1598-1671), cuyo sistema de nomenclatura de 1651 se ha convertido en un estándar. En los inicios de la cartografía lunar había recibido otros nombres. Así, Pierre Gassendi lo denominó Umbilicus Lunaris ('el ombligo de la Luna'); en su mapa de 1645 Michael van Langren lo llamó "Vladislai IV" en honor del rey polaco Vladislao IV Vasa; y Johannes Hevelius lo nombró 'Mons Sinai' en referencia al monte Sinaí.

Fuente: Wikipedia

|